Local environmental advocates who view Waterloo region’s countryside line policy as the gold standard among efforts to protect farmland from urban sprawl say they've witnessed the creation of dozens of new farms over the last decade as a result of the benchmark legislation.

According to the 2016 Census, the City of Cambridge and Wilmot township each reported the addition of 21 new farms since the 2011 Census.

Kitchener-Waterloo added 17 in the same period.

The nearly 100 percent increase in the number of new farms within city boundaries is in contrast to the rest of the province, and Canada, which reported 5 and 6 percent decreases respectively.

But the agricultural policy that has protected the region's farms is under renewed threat from the province's More Homes Built Faster Act, also known as Bill 23, which could negatively impact the Greenbelt and put small farms in check against voracious developers.

That's according to Keep the Greenbelt Promise, a network of grassroots organizations working together to stop urban development in the Greenbelt, on farmland, and in natural areas.

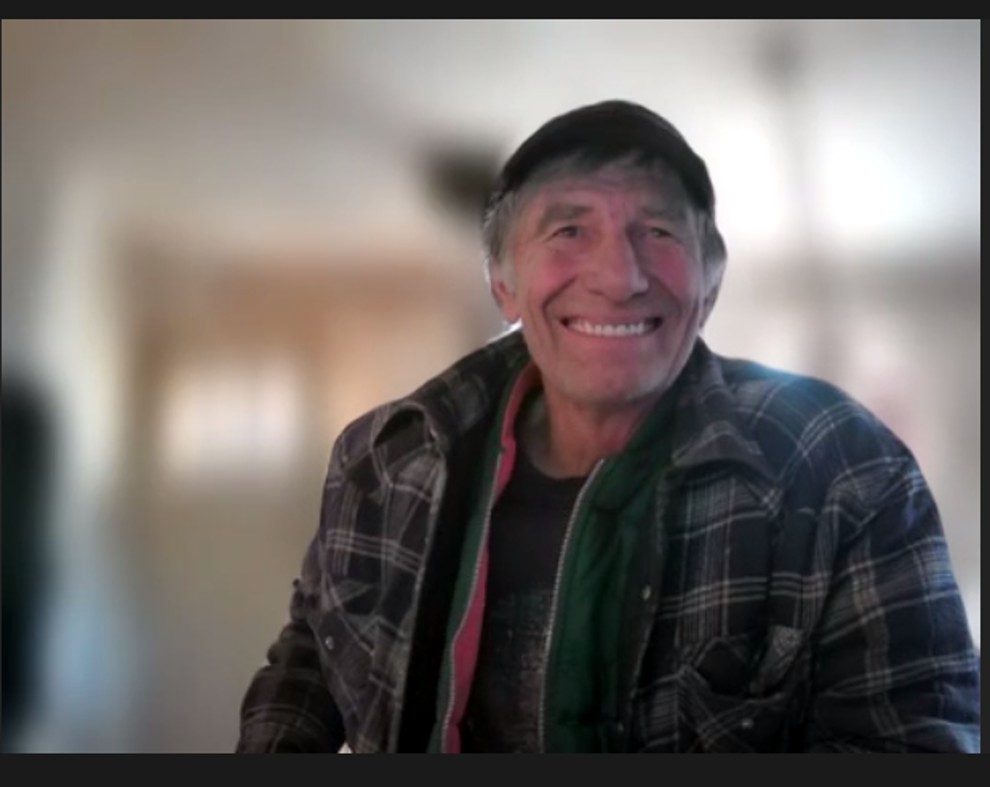

Before the region's countryside line policy, which was drafted in 2009, farmers used to sell land to farmers without much pushback from the region, explained Mike Marcolongo, coordinator of Keep the Greenbelt Promise.

The average value of land used for farming is $50,000 an acre, but for home builders, the per-acre value could reach $1 million.

“For the farmers included in the urban boundary, it could be like literally winning the lottery,” said the advocate for farmland protection. “It could be great for the (seller) farmer, but it's bad for farming or farmland because not only does that farmland go out of production, but it also means that the farmland is fragmented, and they are undermining the farming ecosystem.”

“If you have good planning policies like the countryside line or the Greenbelt, it just means that they're not getting homebuilders' money, which is catastrophic money,” he added.

Marcolongo was one of the speakers at rally in Waterloo a week ago in support of Waterloo region's official plan.

“Our local Conservative MPPs have already betrayed us by breaking their promise and opening up parts of the Greenbelt for development. We can’t let them betray us again by destroying sustainable local plans for the future,” he said at the rally, which was attended by Guelph MPP Mike Schreiner, various environmental advocates and farmers.

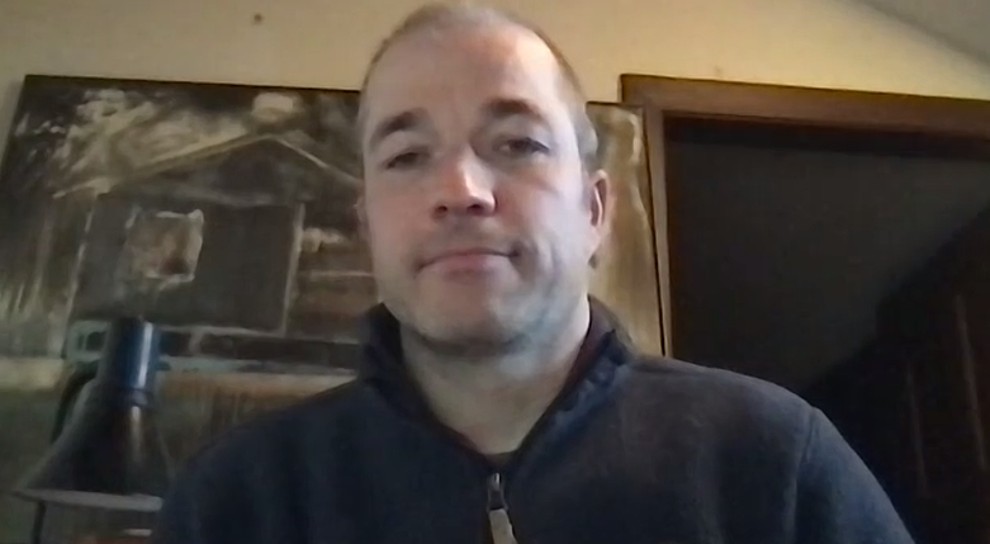

North Dumfries farmer Jeff Stager, who is also director of the Waterloo Federation of Agriculture, told a recent Cambridge council meeting that while in most agriculture jurisdictions in Canada the number of farms “is dropping precipitously,” in the Region of Waterloo the numbers are range bound, and not decreasing.

This trend is evident in the last four Agricultural Census from the last 20 years, he said.

“It is good that the number of farms has stayed steady when nationally they are dropping,” Stager told the councillors and mayor.

“Cambridge is one of the eight municipal governments in Waterloo region. It appears that all eight municipal governments are doing something right when it comes to farm numbers,” added Stager, who also represents the region on the provincial Policy Advisory Council at the Ontario Federation of Agriculture.

In 2016 the total number of farms in the region was 1,374 and the number increased to 1,409 in 2021, according to the census.

With notorious enthusiasm, the former councillor of North Dumfries, said “this industry is active and growing in the region. New people are coming, new business, new energy.”

In fact, the average age of farm operators in Waterloo region is 49.5 while in Ontario it's 55.5.

He highlighted that one in ten farms in the region is using renewable energy-producing systems, such as solar panels, windmills, and natural gas and methane bioreactors.

With the imminent provincial order that the region’s municipalities implement the policies of Bill 23, farmland advocates are afraid it could impact the countryside line policies and the functions of the Grand River Conservation Authority (GRCA).

In an interview with Cambridge Today, Stager said Bill 23 proposes conservation authorities like the GRCA focus solely on flood control, ignoring the fact that it operates important farm programs in partnership with the region, including the Rural Water Quality Program, an arrangement created in the '70s with farmers to keep the groundwater clean.

“This is a model developed in the region that would benefit all areas of Ontario if they had the same program. This program model could also be used for preserving wetlands, species at risk, carbon sequestration and other environmental goals that society may want,” Stager said.

In this vein, Marcolongo stresses that farmers are the “kidneys” to filter the water that we drink in our communities. “The more you build on that land the less there is that recharge function.”

For this reason, he expressed concern that the province “is about to overrule good planning at the regional level. It undermines good farming; it undermines good planning.”

He went further and said that the Ontario government is using the housing crisis to basically “enrich and only listen to developers, who are well connected to their party, unfortunately. It is often about politics, power, and money.”

For his part, Stager has more questions than answers about Bill 23.

“How would this program exist if the Conservation Authority does not do it? Does Bill 23 say, for example, that now the City of Cambridge has to do the Rural Water Quality Program? Will these programs be lost if Bill 23 goes through?”

Knowing that the regional Waterloo plan from the provincial government will be released soon, farmland advocates fear that it could include “a significant urban expansion.”

Marcolongo and Stager agreed that Bill 23, which was approved in a month last fall, had “very little consultation.”

“A lot of stakeholders including agriculture stakeholders were left out of those consultations. They had wanted to delegate to present their concerns to Queen’s Park, but they didn't have the opportunity,” said Marcolongo who worked 18 years as a policymaker for the Ontario Public Service.

Stager completed the idea by saying that regarding the urban expansion in the Greenbelt, the Ontario government is moving “too fast, too quickly, without enough consultation.”

“Farmland is farmland, whether it is inside or outside the Greenbelt,” said Peggy Brekveld, president of the Ontario Federation of Agriculture (OFA), to the Standing Committee on Heritage, Infrastructure and Cultural Policy when talking last November about the impacts of Bill 23 on farmland.

Her remarks included data from the last two censuses—2016, and 2021—and she highlighted that during that time frame, “we lost 700,000 acres because of the sprawling cities.”

She added that the urban boundary expansion announced will use up more farmland. And “once it turns into housing and development, it never goes back to farmland.”

Brekveld accused that at some point “we put shelter over food and that doesn’t make sense. Both matter. We have to plan for both.”

Even though she advised that farmland, agricultural land and local food are “critical to our future in a growing province,” Bill 23 was approved 12 days after her presentation.

While Waterloo region awaits the province's response to its official plan, advocates are planning more public actions to protect farmland.

Keep the Greenbelt Promise is planning another rally on the April 22 weekend on Earth Day.

Marcolongo accuses Bill 23 of undermining everything good about the region's official plan.

"It will lead to more speculation by housing developers on farmland and it will hollow out that farmland in the coming years, resulting in less food security."