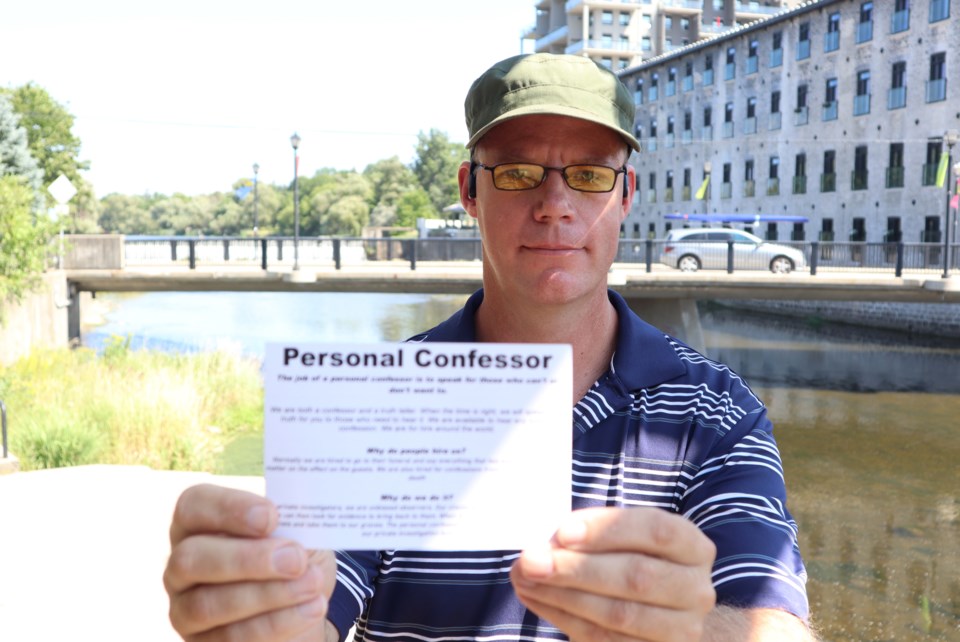

Have a secret you don’t want to take to the grave? Luke Caswell will be your personal confessor.

The 42-year-old Scarborough native has made a living doing several jobs over the years, including a stint as co-owner of the former Afterlife arcade bar in Guelph.

But nothing, he says, has been as interesting as his current business venture as a personal confessor.

“What’s a personal confessor?” you ask.

Part confessor, part truth-teller, his job is to speak for those who can't.

You may have seen his postcards stapled to telephone poles around Cambridge and wondered what it’s about, or immediately thought it was a scam.

Well, it’s not.

Caswell has a website and a phone number and is offering a legitimate service for anyone who might have something more to say from beyond the grave.

Caswell makes no bones about what inspired him to take on the unusual side hustle.

Boredom during the pandemic led him to follow an interest in work as a private investigator.

He picked up his PI license by taking an online course and was about to pursue an agency license that would allow him to take on jobs when he stumbled onto a more unusual career path.

He was working for a friend around this time last year when one of his co-workers, curious about his PI work, asked if he’d heard about the so-called “coffin confessor.”

Caswell said he hadn’t, so the friend sent him some newspaper links about Australian private investigator turned “coffin confessor” Bill Edgar.

Over the last few years, Edgar has been making a name for himself around the world for the unique services he offers, particularly as someone who speaks on behalf of his dead clients.

What he’s asked to say is usually something the people who hire him didn’t have the courage to say when they were alive.

Edgar has confessed everything from a client’s homosexuality to an audience of the dead man’s biker buddies, one of which was his lover, to arranging a face-down display of a client’s naked body at an open casket funeral, complete with a sign taped on his backside saying “kiss this.”

Sometimes the request can be as simple as announcing how much money the beneficiaries stand to inherit, or sticking a needle in a client’s body to prove they are dead.

Many times, Edgar's revelations about his clients have left funeral guests in shock; an ongoing affair with a best friend’s spouse, a secret hatred for a family member, the illicit source of a client’s wealth.

Then Netlflix took notice and began developing a fictional series based on Edgar’s exploits.

The idea so intrigued Caswell, that he began adding the same services to his burgeoning PI business in January.

So far, Caswell’s funeral gatecrashing experiences haven’t been as salacious as Edgar’s, despite charging up to $10,000 for each job depending on the possible outcome.

He only advertises with his postcards and website, tacking the cryptic advertisement to utility poles wherever he might be for his main gig in the construction industry.

That’s what brought him to Cambridge over the last month where he’s been distributing his postcards wherever he can.

Now Caswell is hoping his personal confessor business takes off, so he won’t have to jump through any more legal hoops to become a PI.

He goes into each job ready for the worst and gets signed letters from his clients to prove he was asked to do each task.

Ideally, he'll play a recording of his client asking funeral guests to listen to what he has to say.

In the three times he’s been hired as a truth-teller, it’s been to out gay men and admit to their affairs.

And only in one of those cases did the family react badly to news the man in the casket had really been in the closet.

“One person spat at me and called me the devil,” Caswell says. “That’s the one I would have charged more.”

Since his delivery is “all very straight and to the point,” he says he doesn’t tend to think about what the reaction of his audience might be.

“I don’t stay long. I go in and say what they want me to say and leave,” he says, disappointed there aren’t more exciting stories to share yet.

“I really want something dramatic to happen one day.”

Most of the jobs he’s taken on as personal confessor involve scattering ashes on behalf of a loved one who is either out of province, infirm, or otherwise unable to do the task themselves.

“Generally, I don’t ask,” he says. “It’s none of my business.”

For that service, he charges based on the length of the trip and says he’s scattered remains about a dozen times, from the shore of Lake Huron to the Atlantic Ocean.

He’ll research the legality and feasibility of each request before he accepts the job, adding that he only had to break the law once on behalf of a client who wanted his ashes scattered at his childhood home.

Knowing that he’d likely be turned away by the current owner of the property and wanting to fulfil the man’s last wish, he snuck into the backyard of the home and dumped the bag of ashes in the grass.

In June, a woman hired Caswell to deliver a pizza to her husband with her wedding ring taped inside the box along with a sign asking for a divorce.

The client and her husband were already separated at the time and she wanted the pizza delivered to her husband while he was watching a Montreal Canadiens playoff game with friends.

“It was a bit of a harsh way to give back the wedding ring,” Caswell admits. “I have no idea who opened the box.”

Asked if there’s anything he wouldn’t do for a client, he says anything illegal is off the table.

It's really only limited by money and imagination, he says. “It would really be a matter of where and how much are they willing to pay."

Private item pick-ups are a “don’t ask, don’t tell” situation, but he admits speculating about the contents of a few packages he’s picked up or delivered.

In one case he was asked to burn what he thinks was a box of financial documents.

“I'm not removing drugs, bodies, guns, clothing with blood on them,” he explains on his website.

Caswell hasn’t told many people about his new job and wonders how his family might react to the news given its somewhat sensitive nature.

"One side of my family is fairly religious," he says, smiling. "So, I'm not sure how they'll take it."